essays

Everything You Wanted to Know about Book Sales (But Were Afraid to Ask)

An In-Depth Look at What/How/Why Books Sell

Publishing is the business of creating books and selling them to readers. And yet, for some reason we aren’t supposed to talk about the latter. Most literary writers consider book sales a half-crass / half-mythological subject that is taboo to discuss.

Most literary writers consider book sales a half-crass / half-mythological subject that is taboo to discuss.

While authors avoid the topic, every now and then the media brings up book sales — normally to either proclaim, yet again, the death of the novel, or to make sweeping generalizations about the attention spans of different generations. But even then, the data we are given is almost completely useless for anyone interested in fiction and literature. Earlier this year, there was a round of excited editorials about how print is back, baby after industry reports showed print sales increasing for the second consecutive year. However, the growth was driven almost entirely by non-fiction sales… more specifically adult coloring books and YouTube celebrity memoirs. As great as adult coloring books may be, their sales figures tell us nothing about the sales of, say, literary fiction.

This lack of knowledge leads to plenty of confusion for writers when they do sell a book. Are they selling well? What constitutes good sales? Should they start freaking out when their first $0.00 royalty check comes in? Writers should absolutely write with an eye toward art, not markets. Thinking about sales while creating art rarely produces anything good. But I’m still naïve enough to think that knowledge is always better than ignorance, and that after the book is written, writers should come to publishing with a basic understanding of what is going on. Personally speaking, my knowledge of the fundamentals of publishing helped me not even think or worry about book sales when my own book was published last year. And since I need a reason to justify the time I’ve spent dicking around on BookScan, here is my guide to everything you wanted to know about book* sales (but were afraid to ask).

*Because “books” is an impossibly large category covering everything from Sudoku puzzles to C++ guides, I’m going to focus on traditionally published fiction books in this article.

THE BASICS

What is a book sale?

Wait, you say, everyone knows what a book sale is. Ah, yes, but, what this section presupposes is… maybe you don’t? Actually, one of the things that makes the conversation about book sales so confusing is that there are several different numbers thrown around, and often even people in the publishing industry completely confuse them. Here are four different numbers that are frequently conflated:

1) The number of copies of the book that are printed.

2) The number of copies that have been shipped to stores or other markets like libraries.

3) The number of copies that have been sold to readers.

4) The Nielsen BookScan number.

These numbers can all be wildly different. It’s not uncommon at all for a publisher to, say, print 5,000 copies, but only sell 3,000 copies to bookstores/other markets, of which, 2,000 copies are actually sold to customers. Meanwhile, BookScan shows 600 copies sold. And we haven’t even gotten into ebooks yet (more on that later).

What’s the actual number of books sold? Well… basically a combo of 2 and 3, plus ebook and audiobook sales. A publisher sells books to retailers like bookstores, but also to some institutions like libraries. However, retailers normally (though not always) have the right to return unsold copies. So some copies that are “sold” will eventually be unsold. (On author royalty statements, a certain amount of money is always withheld as “reserve against returns.”)

While this is basic, it’s surprisingly common for authors and publishers to either intentionally or unintentionally confuse these numbers: brag about their sales while citing the print run, for example. On the other hand, the media almost always references the BookScan number without any context about how wrong that number can be.

What Is BookScan and Why Should We Care?

In my hypothetical above, the Nielsen BookScan number, is the least accurate. It’s the furthest away from the “true” sales of the book. And yet, if you read any articles on book sales it is precisely the BookScan number you will see. This is because while publishers and authors (via royalty statements) have access to the real numbers, they are almost never released to the public or to rival publishers. Thankfully, there is Nielsen BookScan, an industry tracking tool that records point of sales based on ISBNs. (Yes, this is the same Nielsen of TV’s Nielsen ratings.) People in publishing can use BookScan to get a general sense of what books are selling, the health of the industry, or tear their hair out in frustration while looking up the sales of their rivals.

So Why Can BookScan Be So Inaccurate?

Nielsen BookScan counts cash register sales of books by tracking ISBNs. A clerk scans the barcode, and the sale is recorded. Pretty simple.

So why can it be inaccurate? To begin with, BookScan only tracks print book sales. Amazon and other major ebook vendors do not release ebook sales, so basically no one has any idea how those are selling (outside of publishers tracking their own sales). Ebook sales vary wildly from book to book (and genre to genre), but are typically less than 1/3rd of sales. For certain genres, especially science fiction and romance, ebooks can be as much as 50% or more.

Even for print books, BookScan can only do so much. BookScan gets data from most big bookstores (including Amazon and Barnes & Noble), but it doesn’t get all of them. It also doesn’t track library sales — which can be significant — or any sales that don’t go through a bookstore. BookScan itself claims to track 75% of print sales, and that may be true overall. For a popular literary fiction title, for which library sales or hand sales are a tiny percentage, BookScan is probably getting at least 75% or more of print sales. For other types of books, BookScan might record as little as 25% of print sales. Small press books, for example, can sell most of their copies at conferences, book festivals, and direct sales on the publisher’s website or at readings. BookScan misses all of that.

Lastly, BookScan was only introduced in 2001, so numbers for any books published before this millennium are completely inaccurate. (I’ve seen people bemoan the small sales of, say, Infinite Jest compared to some recent bestseller without realizing that.) All that said, BookScan does a good job showing general trends in the industry and seeing which books are doing better than others. But you should keep in mind that total book sales are perhaps twice that of every number listed.

How Much Does an Author Make Per Sale?

So let’s say you bought a book (like, oh, how about Upright Beasts by Lincoln Michel), how much would the author make? Author royalty rates vary, but the industry standard is about 8% of the cover price for paperbacks and 10% for hardcovers (escalating to 15% if sales go well). Ebooks, which have variable pricing, are 25% of the publisher’s take. Now, as an author I’d love for those rates to be higher, but I do think it is important for authors to understand that the majority of the cover price doesn’t go to the publisher. Well over 50% of the cover price goes to the retailer that sells books to customers and the distributor who gets the books to retailers. There is plenty to be said about whether the publishing model could be more efficient, if middlemen could be cut out, etc. etc. But when certain corners of the writing world — such as certain self-publishing ideologues — scream about how publishers are ripping off authors and taking 90% of the pie for themselves, that isn’t really accurate.

Don’t Most Authors Make No Money From Sales?

Correct. Most authors do not make any money off of actual book sales because most books do not “earn out” their “advance.” Traditionally published authors are paid money up front, before a book is released. This “advance” is money given up front to the author out of future royalties so that the author can buy ramen and pay the overdue electricity bill. “Earning out” means the book has sold enough copies that the total royalties (not the total sales) match up to the advance, thus providing a (most likely tiny) trickle of royalty money to authors for all sales thereafter.

This ‘advance’ is money given up front to the author out of future royalties so that the author can buy ramen and pay the overdue electricity bill.

Here’s an example: Writer von Author writes My Big Literary Novel and Big Publishing House Press pays her $50,000 dollars as an advance. The cover price of the book is $20 dollars and her royalty rate is 10%. (In reality it would be more like a ~$25 hardcover at 10–15% followed by a ~$15 paperback at 7–10%, but I’m simplifying.) If the publisher sells 10,000 copies of the book, the total sales are $200,000 and the author has earned $20,000 from royalties… except that she was already paid $50,000 so she is actually at negative $30,000. She doesn’t have to pay anyone back either though, the publisher takes the loss. However, if the book sells 25,000 copies, then the author would earn back her advance and at copy twenty-five thousand and one, she would start earning $2 per book sold.

How Does Publishing Survive If Most Books Don’t Earn Out?

To begin with, publishers survive on a handful of hits. A 50 Shades of Grey here or a Gone Girl there make up for a lot of low-advance books that don’t sell well. This is similar to how movie studios survive on a few massive blockbusters to offset the costs of movies that don’t earn what is expected at the box office. Additionally, the publisher makes money before the author does. Even if the distributor and retailer take, say, 65% of the sale price (and it can be as much as 75%), the publisher is getting 25% to the author’s 10%.

When an article talks about how some huge advance given to a debut author and/or celebrity author won’t earn out, that doesn’t actually mean the publisher won’t make money. (Here’s a blog post breaking down the example of Lena Dunham’s huge advance.) In fact, publishers may give huge author advances on books they know won’t earn out as a way of paying a de facto higher royalty rate.

Take our example above. If My Big Literary Novel sells 20k copies, the author still hasn’t earned back her advance yet the press is taking in $90,000 (35% of cover price minus 50k advance). Of course, the press also has to pay for the printing costs of the book as well as any marketing costs or money spent on cover art before it can even pay the various employees that worked on the book… but you get the general idea.

WHAT DO BOOKS ACTUALLY SELL?

Okay, Let’s Get to the Dirt: What Does an Average Book Sell?

Probably not surprisingly, the answer is… it really depends. The first thing that writers need to understand is that book sales — like advances — are all over the place. This is true even for individual authors. It’s not unheard of for an author to get roughly similar critical acclaim for their first three novels, yet have them sell 10k, 100k, and 10k respectively. Publishing is full of luck, timing, and unpredictable trends. (I mean, adult coloring books? Really?) And even then, publishers give dramatically different amounts of support and marketing even to books published by the same imprint.

That qualification aside, most fiction books published by a traditional publisher garner somewhere between 500 and 500,000 sales. Sometimes less, sometimes more.

Can You… Narrow that Down a Little?

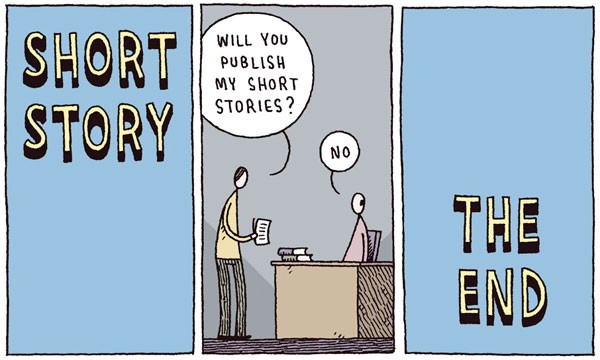

Ignoring the outlier megastars like Stephen King or runaway hits like Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, most novels published by a big publisher BookScan somewhere between 2,000 and 40,000 books. Most short story collections issued by big publishers get about half that: between 1,000 and 20,000.

You can scale this down for publisher size. An independent small press is averaging more like 500 to 10,000 for novels and 300 to 2,000 for story collections. A micro press is more like 75 to 2,000 regardless of book type — at this level, the author’s “platform” and fan base matter more than if the book is a novel, story collection, or poems — with outside successes getting above 5k.

For debut books, you could cut all those numbers in half. Do keep in mind that this is after at least a year of sales. If your book just came out this month, don’t panic yet (and don’t check BookScan for a long time, if ever).

So the Average Novel Sells 20,000?

Well… no. Like baseball salaries or box office returns, book sales are heavily skewed by the minority of books that do really well. If you go into your local bookstore and look at all the books on the various tables, most of those will BookScan between 2,000 and 40,000 after a couple years of sales. The big books by the big names on the tables will get between 100,000 and a couple million.

However, most books struggle to find adequate distribution, much less coverage. Most books do not get placement on tables, and many do not even get to many bookstores at all. The majority of traditionally published novels sell only a couple thousand, if that, over their lifetime.

What Constitutes “Good” Sales?

As with anything here, we need qualifications. What constitutes “good” sales is entirely dependent on what type of book you are publishing, what size your publisher is, and what your advance was. 5,000 copies of a short story collection on a small press is a huge hit. 5,000 copies of a novel from a big publisher that paid a $100,000 advance is a huge disaster.

You also need to factor in the format. Selling 10,000 hardcover is worth more than 10,000 paperbacks. For ebooks, prices can be all over the place, even from a major publisher.

Qualifications aside, if you are a new writer at a big publisher and you’ve sold more than 10,000 copies of a novel you are in very good shape — as long as you didn’t have a large advance. It should be easy for you to get another book contract. If you sold more than 5,000, you are doing pretty well. You’ll probably sell your next book somewhere. If you sold less than 5,000, then you could be in trouble with the next book. (Although it is, as always, dependent on the project. If a publisher loves your next book, they may not care about previous sales.)

The smaller the press, the more you can scale down. One publisher of an independent press told me that most indie press books sell — not BookScan — about 1,500 copies, with 3,000 being good sales. Even then, the publisher stressed, an author selling 3,000 is really just paying for themselves. To be contributing to the operations of the press, they’d need to sell over 5,000.

What Do Acclaimed, Buzzed-About Literary Books Sell?

So let’s say you jump through the hurdles of writing a book, getting an agent, and selling it to a respected press, AND you become one of the handful of books that is well-reviewed in big outlets and buzzed about in the literary world. How many books will you sell?

Most people would be surprised at the drastic range of book sales even among the books that people are buzzing about. If you took the ten literary fiction books that all the critics, Twitter literati, and well-read friends are discussing, their BookScan numbers might range from a couple thousand to 100k. Last year, NPR looked at the book sales of the Pulitzer Prize finalists and found the books ranged from under 3,000 to low six figures.

If you took the ten literary fiction books that all the critics, Twitter literati, and well-read friends are discussing, their BookScan numbers might range from a couple thousand to 100k.

That’s a small sample though, so I went through the BookScan numbers for every fiction book listed on the New York Times 100 Notable Books of 2014. I used 2014 instead of 2015 to make sure each book had at least 12 months of sales. No list is perfect, but the NYT list includes story collections and small press books alongside the big name literary authors and award contenders. 2014’s list includes names like Haruki Murakami, Lydia Davis, Marlon James, and David Mitchell as well as small press debuts by Nell Zink and Eimear McBride. It’s a good sampling of the “books that people are talking about” in the literary world.

The BookScan sales of those books literally ranged from 1,000 to 1.5 million, with an average (mean) of just over 75,000 copies sold per book. That 75k number is pretty skewed by the existence of Anthony Doerr’s runaway literary hit, All the Light We Cannot See, which sold over 1.5 millions of copies. (The next highest book was about 270,000.) If we remove the best and worst selling books on the list, we get a mean of 46,550 copies and a median of 25,000 copies.

(Once again, I’ll remind you that these are BookScan numbers for books published in 2014. The actual sales totals will be moderately to significantly higher depending on the book, and all of these books should continue to sell copies over the years.)

What If You Are a Finalist for a Major Award?

Let’s say you really hit the jackpot and are a finalist for the Pulitzer, what kind of sales would you get? Again, the range is huge. I looked up five years of nominees (from 2011 to 2015) and the range was 5,600 to over 1.5 million (yes, All the Light We Cannot See again). The mean was 250,100 and the median was 72,300. For the National Book Award, the mean was 178,600 and the median was 91,318

For comparison sake, I checked the finalists for science fiction’s prestigious Nebula awards. They ranged from 2,100 to 387,900 with a mean of 35,600 and a median of 12,300. That’s surprisingly less than the major literary awards, despite the frequently heard claim that genre fiction is more popular than literary fiction. (Although keep in mind that science fiction ebooks typically sell better as a percentage of total sales than literary fiction ebooks do.)

What Does a #1 Bestseller Sell?

On average, a lot more. I checked the BookScan sales for all the books that hit the #1 spot on the New York Times list in 2014 and the mean sales were 737,000 with a median of 303,000. The top selling book was, as you can probably guess, 50 Shades of Grey at nearly 8 million. But the lowest was only 62,700, meaning more than 50% of NBA or Pulitzer finalists sold better than it. In fact, a whole lot of the 2014 literary award finalists sold better than bottom 2014 best sellers. If that’s confusing, remember that this is the list of books that were the best selling book in the country for one week, not for the whole year. Sales of commercial fiction books are often far more concentrated than the sales of popular literary fiction books, the latter of which can have very long tails.

Once again, I want to stress that these totals are perhaps 75% of book sales and do not include ebook or audiobook sales.

What About Short Story Collections? No One Buys Those, Right?

It’s a truism in the literary world that no one buys short story collections, and that even when you sell a collection a publisher will only buy it so that your future novel will do better. I myself have always believed this to be honest, even though I wrote and published a short story collection. However, looking at the data it actually seems that while fewer story collections sell, the ones that do can sell almost as well as novels. The seven story collections on the NYT 2014 list had a median of 23,000 BookScan sales… only 2k less than the median novel. When I expanded the data to include short story collections from the 2013 and 2012 list, the average sales were 53k and a median of 22.5k.

So All the Publishers that Rejected My Collection Are Fools!

Well, no. Those are mostly collections by buzzed about debut authors or established older writers. As I said, fewer story collections sell (although fewer are also published) and the ones that don’t sell fail harder than novels. And there’s a cap on story collections. No story collection is going to sell millions of copies like the biggest novels. All of the authors whose collections I counted in the last section sold better as novelists if they had novels out. Since big publishers survive on the few break-out books, it makes more business sense to bet on novels or push authors to write novels instead of stories. Whether that’s good for the culture or the art of literature is another question…

Still, it was heartening for me, as a lover of short stories, to see that collections from authors like Junot Diaz, Alice Munro, and George Saunders can BookScan over 100k, and a collection by someone like Stephen King can reach a million. (In fact, having looked at a lot of sales data I’m convinced Stephen King is the best-selling living short story author in America and probably the world). More importantly, great short story authors like Kelly Link, Lydia Davis, Aimee Bender, Jim Shepard, and so on will BookScan between 10 and 50k… which is comfortably in the range of what acclaimed literary novels sell.

How Does Genre Fiction Compare?

I’ve talked before about how the idea that literary fiction is a tiny niche market and that the various genres sell more is largely a myth. “Commercial fiction” — which is not a synonym for genre — can sell a lot more, especially when we are talking brand name like John Grisham, James Patterson, or Danielle Steel. YA fiction is also having a much-discussed boom these days. But for most writers of adult science fiction, romance, fantasy, and the like, the numbers will be roughly what I’ve listed in this article.

How Does Non-Fiction Compare?

Non-fiction is an insanely huge category that encompasses everything from craft books and joke books to travel guides and memoirs. While there is some variation in average sales between different types of novels, non-fiction sales are entirely dependent on which of the 1,000 types of non-fiction books you are talking about. I’m afraid I just can’t help there, except to say that what you might think of as literary non-fiction — lyric essay collections, memoirs, etc. — will be roughly similar to the numbers listed here.

What About Self-Publishing?

Like non-fiction, self-published books vary so wildly that they can’t really be generalized. If you publish your book through an established press, you can most likely guarantee a certain level of professionalism, distribution, and hopefully coverage for your book. Self-publishing, on the other hand, contains both professional full-time authors who spend time and money marketing their books as well as people who just think it would be fun to put an ebook up on Amazon and never spend any time marketing. Overall, self-published books sell far far less (in part because the majority of the market is still print, and it’s near impossible for self-published print books to get a foothold in stores), but of course their cut of each sale is much higher.

Which Sells More: Hardcover, Paperback, or Ebook?

Another surprising (to me at least) fact from the data I looked at is that books quite often sell the same amount in hardcover and paperback editions. If a book truly takes off, the paperback sales will eclipse the hardcover many times over. But for most books that are published in hardcover first, the paperback sales will be close to the same. Perhaps that’s a feature of the ebook era where readers who prioritize an affordable option will often choose the ebook?

As for ebooks themselves, the sales aren’t available publicly anywhere so it is impossible to say. According to a recent survey, ebooks account for about 20% of the total book market. From talking to publishers and authors, it seems ebook sales are erratic and — as a percentage of overall sales — vary wildly from book to book, publisher to publisher, and genre to genre. To add even more confusion, ebook prices fluctuate a lot more than paperback or hardcover. It is simply hard to pin down. For most traditionally published books, the percentage of sales that are ebook instead of print is somewhere between 10% and 50%.

So What Does All This Meeeaaan, Man?

I often hear that fiction is basically just an irrelevant niche and no one reads books at all. Now that we’ve looked at the numbers, well… I guess it depends on your point of view. If the average well-distributed novel is BookScanning only 10,000 copies, that seems pretty niche. Then again, there are plenty of industries where sales of 10k per product would be respectable. And we have to remember that the actual number of sales might be 20,000, and then maybe 30,000 people have read the book since plenty of people use libraries, pirate, or borrow books from friends. Every year, dozens of new books sell 100k copies on BookScan, and a couple sell a million. A recent Author Earnings report suggested maybe 4,600 writers earn 50k a year off of book sales alone. Not so shabby, maybe, until you realize that about that many MFA students graduate each year. Then again, that’s just looking at book sales, and not money made from freelance writing, speaking engagements, teaching classes, or other author income streams. And honestly, even getting a thousand strangers to read something you poured your heart and soul is pretty okay. Bottom line; who knows what any of this means, but at the very least if you are a newly published or aspiring author you now know the world you’re going into.

As for me, I’m going to get back to work on a weird novel that will never sell, but, hell, is damn fun to write.