news

On The Vanguard

All fiction was about the same thing to Frank Wilder: the crime of his never having been published. Once a reader advanced beyond the great divide of 1945 to enter the furious stew of the modern moment, any novel, Frank felt, was fair game to be scorned. He thought often on the direction of American Literature in the last half century, the opposing poles represented by Mailer and Salinger; the slow death of the important American novel through the 70s and early 80s, culminating in the election of Ronald Reagan as president and, across the Atlantic, the ascendancy of Martin Amis; the recognition of the Academy Awards Ceremony in Los Angeles as a forum of the greatest artistic seriousness; the recent onslaught of poseurs with their image-driven facsimiles of literary gravity, all of whom Frank took the liberty of referring to as “that guy,” regardless of gender: Kerouac (too vacuous), Percy (too Christian), Capote (too jaded), Pynchon (too cartoony), Wolfe (too bombastic), Updike (too flighty), DeLillo (too male), Roth (too Roth), Morrison (too praised), McInerney (too clipped), Rushdie (too shallow), Coover (too madcap), Oates (too morbid), Wideman (too fevered), Moody (too threadbare), Moore (too much), Franzen (too withering), Homes (too demented), Lethem (too ridiculous), Hempel (too elusive), Johnson (too tangled), Munro (too perfect), Chabon (too indulgent), Lahiri (too successful); the list went on — not one of them like him, not one of them just so. On more gracious days he could admit to the merit of a global contemporary like Arundhati Roy for having written one good novel, and then quit — and, when inclined to reach further back into the past, Fyodor Dostoevsky, for the sheer breadth of his comedy and rage. In the end, Frank’s unsteady feelings before a fictive page amounted to one certainty: there had to be a place for him.

“A writer of considerable talent”: the words that had brought Frank to Brooklyn. It seemed like decades ago that someone, a high school teacher, inscribed them on a story he had written, and only Frank had not forgotten. He took the praise to heart, held it there and, upon graduating from college, moved with his girlfriend to Park Slope.

In the back of their narrow studio, across the open entrance to the kitchen, hung a tattered American flag a Republican uncle had given him when he turned nine. The flag had touched the ground many times since the days when he raised it at his father’s behest — up the fifteen-foot pole next to the pool in the backyard that rang out when the rope snapped against it. The colors on the flag were faded, but, aesthetically, it pleased him. With the lights in the kitchen on, and those in the foyer out, red and blue prisms fell across the weathered couch and framed photographs on the wall.

Sometimes, Frank reclined on the couch alone in his favorite trousers, slate grey and orange plaid, with forest green suspenders, frayed and faded from nearly a century’s wear. The attire had belonged to Frank’s grandfather, Irving Wilder, himself once an aspiring novelist. Other times Frank shared the couch with Lena, his girlfriend — also his best reader — and admired the aleatoric way that the flag’s color scheme embraced her angular bangs.

Their Park Slope apartment was located in the southern outskirts of the neighborhood. Frank bought a queen-sized mattress and scarlet sheeting and laid it right on the floor. Outside, men and women in seemingly identical striped, sleeveless shirts pressed down the block. From a window, Frank watched them go by. It was what he did instead of smoking cigarettes. An Off Track Betting depot around the corner attracted low-talking clusters of wishful thinkers. Cats peeked out from under the chassis of parked cars.

“My boss is the plague in human form,” Lena said one day over lunch, at a sidewalk café, “She’s like the human dating virus. Literally everyday, the woman has a new adventure to embarrass herself with. It’s just so — ugh. Incessant. She doesn’t know how to stop! She can’t!”

Lena worked as an editorial assistant at a widely purchased fashion mag; she harbored serious respect for ripening trends. Her boss and her father were two favorite topics of conversation. Seeing Frank chafe under the weight of his modestly paying job, a visible discomfort in letting her settle the bill, she often mentioned her father.

In the mornings, she began more and more frequently to allude to the pigeons outside on their kitchen windowsill. They clustered there and cooed, as light emerged on the earth from some unseen source. Frank could hear them as he turned again to face his Santa-beard of shaving cream in the bathroom mirror. His expression was serious.

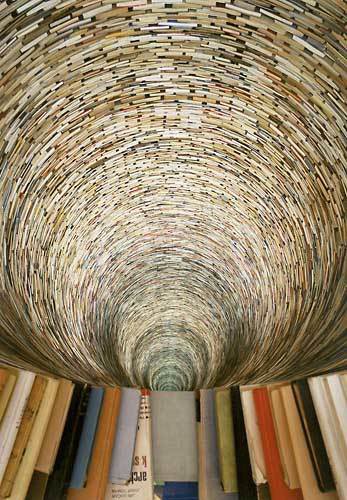

During the week Frank earned pay as the guy at the information desk of the local branch of Burns & Porter, a corporate super-bookstore whose name possessed such currency in the modern era that to invent a fictional alternative for it seemed hysterically futile. In the stories Frank wrote about someone working for Burns & Porter, the store was always Burns & Porter, never something else. Both in his stories and real-life, people arrived after having seen mention of a particular novel’s title on daytime TV and ordered one or two of those to go, maybe grabbing the famous face magazine Lena worked for off the rack while waiting in line for check-out. Modern fiction gone bad, image reigning supreme, nobody knew anything anymore, thought Frank, coolly returning the look of another customer whose unconscious gaze had affixed on his vintage suspenders.

Work, such as it was at Burns & Porter, consisted mainly of learning to obey managers and the older hands. Another important facet of the job was feigning solicitousness toward every sort of idiot customer. It drove Frank nearly mad; on the page his characters courted ever deepening darkness.

**

This morning they are at the breakfast table that Lena insisted be placed in one corner of the narrow kitchen. Granola crunches between Frank’s teeth, the slices of banana soft and sweet on his tongue. Before breakfasting with Lena, Frank had never been a guy to include banana in his breakfast bowl. Seemed somehow too dainty. But with her around, things are different.

Lena is peering at him, or maybe past him, toward the grated window immediately behind him. She flutters the open section of the Sunday Times, then closes it, letting it rest atop the others in her lap. She takes a two-handed sip from her coffee mug, lowering her head to its steaming mouth.

Then she looks at Frank and asks, “Do you love me?”

Frank sets the spoon back in his breakfast bowl. Her eyes hold his for a moment, desperate with the question, then she seems to recede into herself, gone vague in some interior space.

Frank imagines how he will describe her in the novel he is writing; how her type will become the type that all the young seekers emulate; how his novel will be a smash, resurrecting the pursuit of serious fiction across the nation, undoing years of shame and neglect; how the two of them will jump together into a fountain, like Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald; how they will, in this manner, alter history’s irrevocable course; and how, finally, as figments on a page, be granted life eternal.

What Frank says to her now should resonate. He pictures the day awaiting him — the hours in the information booth, followed by a solitary lunch, then the evening before his keyboard, where he will catapult himself once more into empty space, beating back all doubt to bring home the future lives that he and Lena must share.

“Love is funny,” he listens to himself say, “Isn’t it? Just what two people make out of nothing.”

From the sill the pigeons coo.

– Jeff Price is a freelance writer and editor.