Books & Culture

The Spatial Poetics of Nintendo: Architecture, Dennis Cooper, and Video Games

by Adam Fleming Petty

The Indianapolis Museum of Art has an outdoor venue called 100 Acres. It features large-scale works that interact with the natural environment, including an enormous skeleton spread out across a field. (You may have seen this in the film version of The Fault in Our Stars.) My favorite is an installation called Park of Laments by Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar. You enter the park by going down a ramp, giving you the sense you’re entering a football stadium to the cheering of thousands. But when the ramp curves upward and deposits you in the park itself, there is an eerie quiet. You stand in the center of a carefully tended lawn. Enclosing the park are what look like the ramparts of a castle. You walk around the park, inspecting the ramparts for some sort of message, unable to shake the sense you are waiting for something.

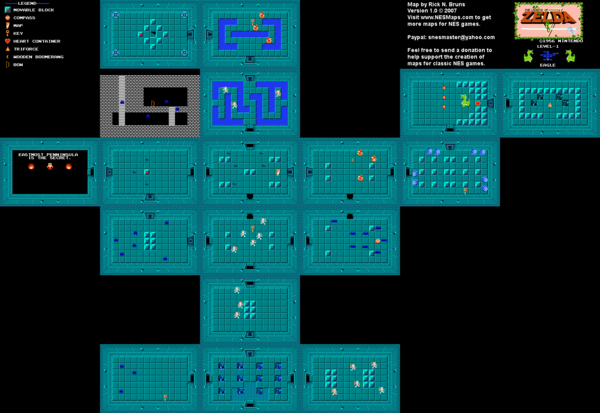

Jaar intended Park of Laments to be a space of seclusion where one could contemplate historical trauma — far from an abstraction for someone whose native country was overthrown in a military coup. The first time I visited, however, my thoughts were not quite so lofty. The space reminded me of The Legend of Zelda. My anxious calm was similar to how I’d felt the moment before a boss battle, checking inventory one last time before Ganon stormed out of one of the paintings on the walls, riding a red-eyed horse.

This sensation was one I often felt when playing video games in my mediated adolescence, encountering the world through controllers and screens. The feeling was a reaction to a physical environment: the haunted houses of Super Mario World, the Esper Factory of Final Fantasy III. Video games provide an aesthetic experience, and the effects they produce in this consumer most closely resembled the silent awe I feel in the presence of the most powerful architecture, sculpture and installation art. It sounds counterintuitive, since video games are often constructed from temporal elements — one level to the next, racing against the clock. But they strike me as an essentially spatial medium.

…in the ongoing argument that would claim video games as an authentic, legitimate art form, the medium’s narrative aspects have been overemphasized while its structural aspects go neglected.

Of course, video games, like movies, are an amalgam of many different media. Some lean on the time-based pleasures of narrative while others resemble the spatially-oriented work found in galleries and museums, visual and plastic arts that bend and shape the space surrounding them. But in the ongoing argument that would claim video games as an authentic, legitimate art form, the medium’s narrative aspects have been overemphasized while its structural aspects go neglected.

Why is this the case? Blame Steven Spielberg. In an interview from 2004, Spielberg was asked when and how video games might reach their maturity as a medium of renown and prestige. He said, “I think the real indication will be when someone confesses that they cried at level 17.” Shedding tears upon reaching a particular point in a game? Sounds an awful lot like a movie, and a Spielberg movie at that. Why Spielberg was deemed the ideal critic for assessing the progress of video games is a mystery, since he infamously gave his approval to the E.T. video game produced for the Atari 2600 in the early 80s, which is now widely regarded as one of the worst games ever made. He’s a symptom more than a cause, however. Cinema is the ubiquitous medium of our culture, training our responses to so many aspects of reality. A book that transports our imagination is “cinematic,” the footage of natural disasters on CNN is said to “look like a movie.” It’s inevitable that video games would be judged by the same yardstick.

So what other critical tools could we use to consider the experience of playing games? What vocabularies could we consult to formulate a theory of videographic space?

Forget movies. Let’s look at fiction, the medium made of nothing more than words.

***

In postwar France, the theorist Gaston Bachelard wrote a study called The Poetics of Space. It examines various physical structures, the house in particular, as they have been depicted in literature. Like the best Continental theory, it draws on disciplines ranging from philosophy to psychology to physics as it describes seemingly familiar environments:

For our house is the corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word. If we look at it intimately, the humblest dwelling has beauty. . . . In short, in the most interminable of dialectics, the sheltered being gives perceptible limits to his shelter. He experiences the house in its reality and in its virtuality, by means of thought and dreams. It is no longer in its positive aspects that the house is really “lived,” nor is it only in the passing hour that we recognize its benefits. An entire past comes to dwell in a new house.

I can’t tell you how many times I reached a level-end boss for the first time only to have the sensation I’d been there already, a room in a house I’d forgotten I’d visited.

Space in video games is not, strictly speaking, physical. It’s made of pixels on a screen, and the movement of objects within it are governed by the algorithms of its central processing unit. This artificiality has the ironic effect of making the world inside of a video game more immediately familiar than the world beyond our living rooms, as if the game is a memory we didn’t know we had. I can’t tell you how many times I reached a level-end boss for the first time only to have the sensation I’d been there already, a room in a house I’d forgotten I’d visited.

Fiction is well suited to representing space in this cosmic-domestic sense, as Bachelard points out. It’s a feature that dovetails with space in video games. Several writers of the last decade or so have drawn on this connection, creating worlds that feel like levels of a video game stripped of goals and objectives. Perhaps the most direct example could be found in Dennis Cooper’s God Jr., a novel whose protagonist literally enters a video game.

Jim, the main character, was in a car accident that killed his teenage son Tommy. His friends and family tell Jim not to blame himself, but they don’t know the truth. Jim was stoned, having smoked up with his son beforehand, and the resulting disorientation caused him to crash his car into a telephone pole, flinging Tommy through the windshield. Jim’s grief and guilt find an unusual expression. Perusing the teenage detritus of Tommy’s bedroom, he finds a notebook containing sketches of a strange, elaborate structure. Jim treats them as blueprints and hires contractors to build the ungainly structure of uncertain function in his backyard.

As work on the structure nears completion, one of Tommy’s friends comes to visit. She recognizes the structure. It’s from a video game, she says, a secret level whose entrance Tommy spent hours trying to find, to no avail. Desperate for answers, Jim plays the game, picking up where Tommy left off. It’s here that the story becomes truly weird. Jim’s consciousness somehow inhabits the game’s protagonist, a shambling bear that recalls Banjo Kazooie, the 3-D platformer for the Nintendo 64. He makes his way through the game, speaking to enemies and anthropomorphic plants, all of them convinced he is a god. But being regarded as a deity still doesn’t allow Jim to enter the secret level that so intrigued Tommy, leading him to wonder about the level’s origin:

What if this game started life as a very different product? What if it were a real work of art that would have changed the gaming world forever? What if it totally freaked Nintendo out? What if they had spent millions of dollars to redo it into something more commercial? What if this monument was part of the old game that nobody noticed until it was too late? What if they just locked the door, rendered these rocks around it, and hoped no one would notice? Maybe it’s a whole world in there like, say, Zion in The Matrix. Or maybe I am just stoned and it’s just a bunch of fucked-up pixels.

Only a building that exists not in physical but virtual space can contain his guilt and shame.

Jim misses his son so desperately that he’s led to build the monument in the outside world, but even this can’t fully express his grief. What offers him closure, or, failing that, finality, is the artificial, immaterial construct as it exists in the game. Only a building that exists not in physical but virtual space can contain his guilt and shame. There’s a kind of transcendence at play as the game exceeds its design to give shape to a father’s grief, bending the space within the game into shapes that neither the native enemies nor the interloping Jim can fully perceive.

This trope of a video game-like environment surpassing its function is one that’s played out in the work of many younger writers with an experimental streak. Think of Blake Butler, whose fiction seems to portray video game characters after they’ve run out of lives. His recent novel 300,000,000 is about a serial killer known as Gretch Gravey pursued by a detective named Flood. Flood searches the basement of Gravey’s house and passes through a portal leading into a counter-America of ash and empty fast food joints, like a video game that’s all background, with no bonus points or power-ups. Matt Bell’s In the House Upon the Dirt between the Lake and the Woods portrays a father who builds the titular house for his wife so they can raise a family there, but when she is unable to conceive, the father must journey into the woods to confront an enormous bear. It’s the best Nintendo 64 game that never got made. And the work of Amelia Gray features houses and basements that taunt their characters with unsolvable puzzles, a sort of existential Maniac Mansion.

The declarative sentence, high-resolution graphics: in the hands of artists, these are tools for portraying inner space, the peaks and valleys, houses and monuments that dot the landscape of the imagination. Sure, story is an important component of both books and games but I’ve often found that my favorite books and games allow me to stop and look around, strolling through paragraphs or pixels like they were coliseums, always with the sense that some part of me has been here before. Bachelard described what we could call this sense of the spatial uncanny like this:

Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.

Are video games poetry? The very question sounds like the setup for a joke. But jokes have a habit of being prophetic. Perhaps this one’s time has come.